The curiosity crisis

February 5, 2019

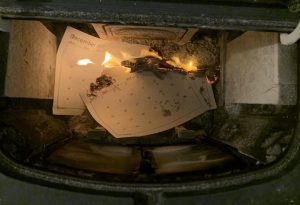

So, we have this cat. Sorry, had this cat.

My family isn’t a pet family. But my sister couldn’t sleep and insisted she needed a guard cat. Loopy and easily influenced from sleep deprivation, my parents conceded, adopting the newest member of the family, Casper. At the time, we were remodeling our house and there were these little cat-sized holes everywhere. Casper loved to explore them. Naturally, Casper went missing. My mom and dad aren’t helicopter parents; they felt that if Casper thought she was old enough to live in the walls, then they would consider themselves the proud owners of a wall-cat. But my sister and I knew something my parents didn’t: Living things need food. And Casper wasn’t eating. The problem then became: How do we get a cat out of a wall in order to save it from starvation? You know, kid stuff. We turned to the fount of all knowledge: Google. As it turns out, catnip and patience were the only tools required for this catastrophe. Yeah, I hate me too.

When Delaney, my sister, gallantly pulled Casper out of her sunken pit, a ray of light struck the tableau like the sun touching down upon Simba in the Lion King, and my sister said, holding Casper up like a newborn prophet, I kid you not- she said, “Curiosity nearly killed this cat. But we saved it.”

Casper is in a better place now: our friend’s house. Her incessant need to explore wall-holes led her to a death-trap. Curiosity did nearly kill her. But our curiosity also saved her. Without our deep internet dive, Casper would have lived up to her name, a friendly ghost.

The double bladed nature of curiosity cuts far beyond the hollow walls of my house. According to Ian Leslie in his book “Curious,” there are two types of curiosity: diversive and epistemic. Diversive curiosity is pure, unfettered inquisitiveness meandering without purpose… into a hole. Diversive curiosity is a baby with a fork and a power socket. When we wonder what our ex is up to and then stalk him/her on Instagram for hours, that is diversive curiosity. When we Google for bits of information and not understanding, that is diversive curiosity. It’s dangerous. It’s detrimental.

Epistemic curiosity, on the other hand, is diversive curiosity all grown up: purposeful and poised. Academia is epistemic curiosity. Literature, experimentation, NASA, empathy: all epistemic curiosity. It’s what we want; it’s what we need.

But, generally speaking, epistemic curiosity isn’t what we have. And this leads me to my primary concern: As diversive temptations become ubiquitous, our epistemic curiosity falls to the wayside, resulting in a populace plagued by the illusion of wisdom and a reality of ignorance.

Moreover, the nature of curiosity dictates a direct trade-off between diversive and epistemic wonder; meaning, when one finds success, the other is met with failure. A diversive-minded community inherently lacks epistemic practices. Historically, mankind has pressed its hand on the delicate balance between the two disparities, consciously favoring the progressive. One example of this is NASA.

Stephen Hawkings once said, “Look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see, and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious.” Hawkings understood that space is curiosity’s playground, endless in potential for discovery.

Furthermore, NASA embodies the tenets of epistemic curiosity; teeming with purposeful ambition, this government entity is the direct result of positive curiosity. We sent a man to the moon! But NASA is dying.

According to the National Office of budgeting and managing, at the peak of the race to space, we funded NASA with 4.41 percent of tax dollars- today, we allocate a dismal 0.47 percent. I’m not great at math- I prefer lunch- but I’m pretty sure that means we, as a nation, are 9.38 times less willing to invest in curiosity than we were in 1966.

The truth of our dying disposition to constructive curiosity is as undeniable as the fact that my cat had to go on anti-anxiety medication. But the question remains: Why is this happening?

That’s a difficult question, so I GTSed it: Googled that… Stuff? And what I found was interesting, to say the least. Did you know there’s a conspiracy that the government can control the weather and your mind? There’s actually so much evidence for this, OMG. So essentially during the Vietnamese war, which there’s another conspiracy that never happened, but assuming that it did, there were these spies, right, that were actually communist robots that controlled the weather with lizards. But then: plot twist! The rain from the artificial weather had mind-controlling chemicals. Why else would people buy bell bottom pants and lava lamps? Think about it.

My point is: there are a lot of distractions on the Internet- echo chambers, informational rabbit holes, or cat-holes, I guess. And worse, we often mistake these distractions as tokens of wisdom.

According to an article published by the Guardian, Google gives users a false sense of insight. Often, the information we acquire via a quick google search is a narrow truth, or a falsehood altogether. But because there is a net gain in knowledge, we feel that we’ve fulfilled our epistemic responsibility. In the process, however, we’ve only fed our diversive curiosity and suppressed its epistemic counterpart.

Ironically, in an age ostensibly defined by enlightenment through the free-flow of information, we’ve never been more blind or less less hungry for purposeful and complete truth.

As we reach for screens instead of stars, we’re also failing to reach out.

Curiosity thrusts us into intellectual endeavours such as NASA, but also motivates us to meet new people, people like our neighbors. And nobody is closer to their neighbors than my grandparents.

They not only know each other, but they look out for one another. I always believed this to be due to the insane amount of time they’ve lived in their house. They say, however, that’s just how it used to be. Neighbors were close.

I don’t know what the heck those flower children were smoking, but I’ve never really met my neighbors. My neighbors, if they exist, are not close to me.

And I’m not alone; according to the Pew Research Center, one-third of all Americans have never met their neighbors. Ever.

We are so stuck within ourselves, so apathetic to the world around us, we fail to reach out to the people living 30 feet from us.

We’ve become islands.

Volcanic islands with the potential to breathe in diversive curiosity and spew hate.

Known as the eccentric host of InfoWars, Alex Jones feeds off the diversive curiosity of his followers. Other than asserting that frogs are being made gay by water poisoned by the government, his biggest claim-to-fame is his accusation that Sandy Hook was staged. Parents are now suing Jones because like-minded individuals have fallen into his diversive trap and have began to harass the parents of the victims of Sandy Hook. Bereaved parents have had to move to private communities to avoid strangers accosting them, asking why they would lie about their child’s death.

Diversive curiosity not only halts innovation and discourages connection; it inspires actions that lack any empathy or humanity, actions so detached from reality and ignorant they paint victims as villians and rob them of their right to grieve privately.

It’s time we ask the question: What can we do?

Just that, ask questions. Go deep. But have a purpose, too.

John Lloyd was a deeply successful English TV producer and director. His life was what most of us imagine to be nirvana: family, financial stability and fame. Despite his comfortable situation, Lloyd woke up one morning completely dissatisfied. Tail spinning in what seemed to be a midlife crisis of epic proportion, Lloyd fell into a deep depression. The recipient of the most prestigious English TV award could be found crying under his desk. But Lloyd was determined to overcome this. So, he took time off work. Spending his days walking and thinking and drinking whiskey… and reading. Lloyd loved to read, but never really got to because of his busy schedule. Little did he know his new hobby would pull him out of his depression like we pulled Casper out of her wall hole.

Reading opened the world to Lloyd. Through books, he satisfied his innate and immense desire to learn. He went deep, exploring topics as disparate as politics and wood varnish. Regardless of the subject, though, Lloyd learned with the intent to understand, not merely know.

In order to live in a world brimming with epistemic curiosity and, by extension, empathy and humanity, we must live our lives like Lloyd: hungry for the truth, the complete truth. For a shallow truth carries us, with a false confidence, to failure. Lloyd knew depth, and, thereby, avoided the plights of diversive curiosity.

We have to dive deep into our curiosity. As deep as NASA’s Rover, Curiosity, plunged into space when it went to Mars. As deep as my grandparents’ porchfront conversations with their neighbors. As deep as my sister’s hand when she pulled Casper out of the wall-hole. We must charge on with direction because the balance between humanity and apathy can only be tipped by profoundly curious hearts.

Shannon graber • Feb 5, 2019 at 7:11 pm

Hi Gage, hey, I am your neighbor, Shannon ! Remember me, with the drawer microwave? You DO know your neighbor, at least a bit….nice article, however! If one wants to know neighbors better, like your grandparents, we must all be willing to give time. Potluck? Keep on writing! Shannon G

Gage Gramlick • Feb 6, 2019 at 8:08 am

Hey Shannon! I do remember you! I love you! I also love potlucks… really food in general. So you know I’m down! Sorry if I insinuated we aren’t close; we just aren’t as close as I’d like to be 🙂