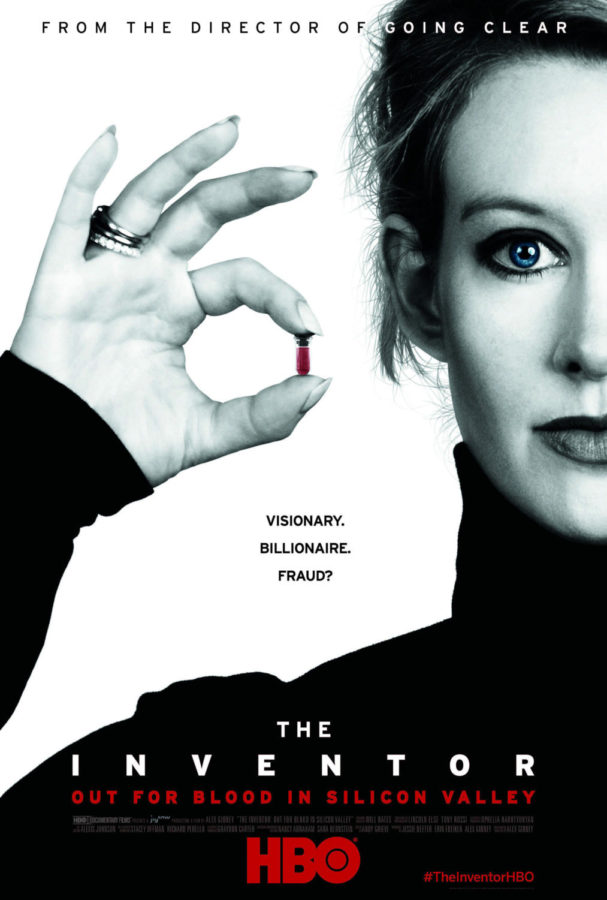

‘The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley’ dives into scandal and fraud

The story of Theranos, a multi-billion dollar tech company, its founder Elizabeth Holmes, the youngest self-made female billionaire, and the massive fraud that collapsed the company.

March 5, 2019

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

The word Theranos; a hybrid of the words therapy and diagnosis. Simple, innovative and simply ahead of its time. Similar to its namesake, once revered inventor Elizabeth Holmes’ $9 billion company was set to revolutionize the healthcare and technological industries by storm.

The Sundance Festival documentary follows the cautionary tale of Elizabeth Holmes and her quest to develop a more accessible method of testing blood. This method would, in theory, require only a blood sample the size of a jellybean to collect data for “over 200 tests.” The machine was given the charming name, “Edison,” which Holmes ideally believed would some day operate within every home in America. Told through first hand interviews from ex-Theranos staff and journalists (including John Carreyrou, who first broke the story and wrote the book “Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup”), reveals a story almost too good to be true.

Previously dubbed as “the next Steve Jobs” and even receiving recognition as “the youngest self-made billionaire” by Forbes magazine, Holmes ran Theranos without significant media attention, until the company’s partnership with Walgreens in 2013. Once in the public eye, the company began to receive legal threats and investigation from the US Department of Health and Human Services. Carreyrou of The Wall Street Journal initiated a several months long investigation after he received a tip from a medical expert who questioned the legitimacy of the company’s blood testing device, Edison, and found that the company was conducting a majority of their tests on commercial analyzers from third parties. Holmes eventually pushed back, attempting to prevent Carreyrou from publishing his eventual “bombshell article,” the first of several to expose the company’s actions.

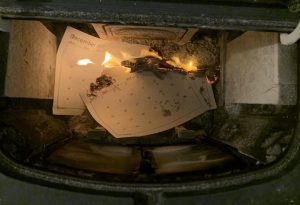

Later, suspected fraud was also detected by the CMS, or Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, banned Holmes from operating or owning a lab for two years, followed by the FDA shutting down the company’s core invention, the Capillary Tube Nanotainer. Other reported ongoing actions include civil and criminal investigations by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California, an unspecified FBI investigation and two class action fraud lawsuits. Yet, Holmes denied any wrongdoing on her or the company’s part.

“I’m interested in the idea that she wanted to do good,” said the film’s director, Alex Gibney. “If you start at the end of the story, she’s a fraud. If you go back to the beginning, you see someone young, idealistic who wants to make a difference. I think you see the danger along the way when the dream and the reality conflict.”

The film focuses a majority of the plot on Holmes’ younger years, during her “eureka moment” as a 19-year-old Stanford dropout. When questioned on her motives and dreams for the company, Holmes stated “… that less people have to say goodbye too soon to people they love.” Turning a blind eye to her indictment by a federal grand jury on nine counts of fraud and two counts of conspiracy, ultimately facing 20 years in prison, do we see someone with a simple dream? Or, rather, a rotten scam artist?