A fish that has never left its tank mistakes the glass for the world’s edge, forever ignorant of the ocean that lies beyond.

We are the fish, and America is the glass.

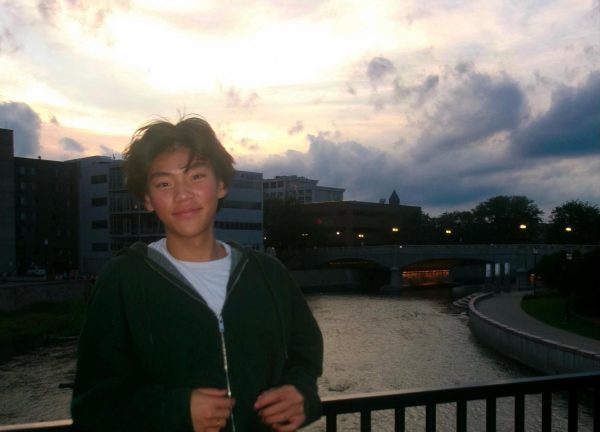

Growing up in America, a country characterized by one of the highest standards of living anywhere in the world, my internalized perspective on the concept of privilege has been greatly distorted and sheltered from the adversity of the world beyond. A deficiency in exposure to contrasting ideas and experiences manifests in my mindset of unacknowledged and oftentimes unintentional ignorance. Students in the United States, including me, are often unable to fathom a lifestyle of true economic hardship and struggle. Access to a quality education, passionate teachers and so many other opportunities are abundant in America, yet a pervasive culture of underutilization and complacency runs rampant. Living in an environment that perpetuates these jarring and extreme ideals breeds a lack of intrinsic motivation, depriving students of a greater purpose and sense of self.

Privilege is an invisible burden we all carry with its weight only manifesting through acknowledgement. Now, the question to be faced is why? What is the purpose of acknowledging privilege if it stands to weigh us down?

For the longest time, this was a question I could not answer until I finally began to direct efforts full of intention to not only educate but expose myself to stories—ones of hardship that I had never bothered to ask about—from the people closest to me: my parents.

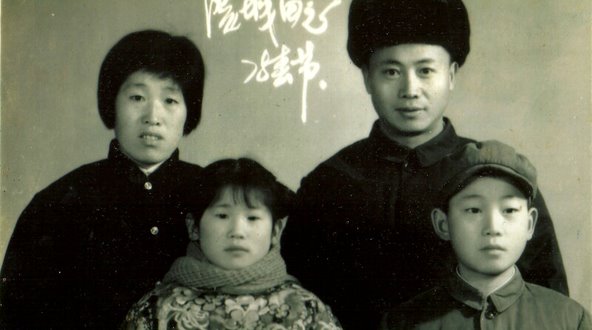

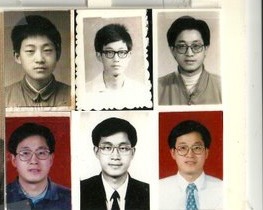

My father, Jianning Tao, grew up in Taoxi, a village tucked deep in the mountains of rural China. It was a place where the earth fed the people, and the people fed the earth in return. The economy was primarily agricultural: life revolved around planting seasons, and families often passed down the same struggles from generation to generation.

“We didn’t have much,” Tao said. “There weren’t enough resources, and the ones we did have had to be shared between too many students.”

There were schools, technically. But the idea of higher education, let alone studying abroad, was absurd to most. The city students had trained teachers and test prep books. My dad had a few worn-out materials and a desk he shared with three siblings.

“If you didn’t push yourself, no one else would,” Tao said. “The system… wasn’t catered for people coming from an [under-resourced] background.”

Early mornings and late nights became routine. There was not a schedule so much as a commitment. Hours blended together as he studied for the Gaokao, China’s national college entrance exam. One test, once a year, that would determine your entire future. And it was not an even playing field. But he studied anyway.

His hard work earned him a spot at a university, and later, a graduate scholarship that allowed him to pursue a PhD in biochemistry in the United States. He arrived with almost nothing: no support system, limited English and no guarantee of success.

“I didn’t know how anything worked here,” Tao said. “But I had already come so far… [so] moving was a risk I was willing to take.”

This was what I inherited, not his hardship but his purpose. He built a life with quiet sacrifice, without ever needing to say it was for me. What is remarkable is that he never used his story to pressure me. Neither of my parents ever have. They don’t expect perfection. They have never cared about something as trivial as class rank or grades. They want me to prioritize my well-being and dedicate myself to anything I choose.

I know I am lucky in that way. Despite the towering mountain they both climbed to get here, they’ve never forced me to carry that same weight. Instead, they let me walk my own path but made sure I’d never have to start where they did.

A gradual understanding blossomed as I learned about their stories: an understanding that allowed me to see higher and further over the illusion of privilege and find something greater that was waiting within.

I used to think work ethic came from discipline alone. But it is more than that. It is knowing what was given up so I could have options. It is waking up early not because I have to, but because I get to. It is approaching every paper, every project, every test with an awareness that my father once studied, hoping to escape a life where education was never promised.

His story echoes in my mind during the moments that matter most—when I am tired, when I am overwhelmed, when quitting feels easier. I do not always succeed, but I never give less than everything I have because I know how easily this could have been out of reach. Because I know that somewhere, a kid like my dad is still waking up before sunrise, still studying in silence, still chasing a dream that feels impossibly far away.

Education, to me, is not just a ladder: it is a debt I owe to those who never had the chance to climb it. My father did not fight for an opportunity just to hand it to me. He fought so that I could learn what to do with it.

This is my inheritance. Not just privilege but purpose.

I have begun to see beyond the glass of my tank, glimpsing the vast ocean that exists outside my immediate experience. I have been shown what lies beyond—not to make me feel guilty for the water I swim in, but to help me understand its true value. In acknowledging both the glass and the ocean, I have found something greater than privilege alone could ever provide: a reason to swim with intention, with gratitude and with a sense of responsibility to the currents that carried my family here.