A brimming bloodthirst

April 5, 2019

On Friday, March 15, a helmet-mounted camera began recording on Facebook Live.

“Alright,” a male voice echoed, turning the clutch into drive with one green-gloved hand, “Let’s get this party started.”

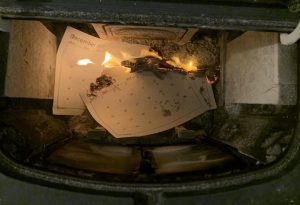

Following a five-minute drive, he pulled into a parking lot and arose from the driver’s seat, leaving his Subaru running. The camera shook as he stepped down and readied his graffiti-littered rifle. Some of the scrawlings were names of mass shooters. “WELCOME TO HELL,” another read.

Footsteps sounded in an ear-ringing echo against the silence of the neighborhood. He approached an arched mosque entrance and proceded to the stop of the steps; the barrel of the gun ascended into the frame.

“Hello, brother,” a worshiper’s voice greeted, his back to the camera. The gunshots commenced, merciless and deafening, and in that moment, hate won.

The livestream of last Friday’s infamous Christchurch shooting, along with the gunman’s 76-page manifesto, spread like an infestation of hate and violence. Major social media standings such as Facebook faced criticism on a higher level than ever before for not removing the video efficiently enough. The corporation rushed to remove the hundreds of thousands of copies like a twisted whack-a-mole. Amongst the waves of hatred clashing at all sides as a result of Facebook’s flawed system, I had a different pressing thought that couldn’t be left unanswered: what drives people’s infatuation with this footage?

Firstly, there’s a sense of rebellion in knowing we’re doing what authority tells us not to, like rushing out into the halls of LHS to witness a catfight despite the incessant protests of teachers. But beyond that, it’s built into our biology. Humans crave the shock factor, something that can give us an emotional high, whether it’s good or bad. There’s a whole community on the dark web that gets a kick out of seeing massacres, cannibalism and hate crimes. Having an audience that craves increasingly shocking violent content pushes these mass-shooter types into creating that content and making their mark within the community. These killers want fame.

They want to be gawked at, to be discussed on national news and go down in history as powerful and almighty. And, by releasing the mosque shooter’s manifesto, by uttering his name and ogling at him like children at a zoo animal, it made me realize that it’s not about Facebook. It’s about our culture.

The French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) is now suing Facebook and YouTube over the mosque footage. Is it deserved? Maybe. But before we unleash our pitchforks, we must first look in the mirror. The problem doesn’t start with the downfall of social media corporations; it starts with how we should acknowledge the attackers within that media. Better yet, we don’t acknowledge them at all.