The unwanted gift of being “gifted”

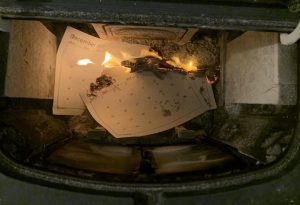

Gifted students learn in different ways, often participating in additional activities altered to allow them to learn the way their brains were made to.

October 22, 2021

At the beginning of fourth grade, my teacher told me, “You will learn something big this year.” Before each lesson, I would sit eagerly, questioning if today would be the day that I learned that “big thing,” but the day never came.

In second grade I was enrolled in the gifted program, called ULE at the time. Once a week, I would walk down the hallway to a small room where all of the students in the ULE program met and did different activities that were specified for us. This became my routine for all of my elementary school years, and participating in the meetings became the highlight of my weeks. The intentions of the program were to encourage us to want to learn more in the way our brains were wired and provide us a safe space where we could collectively bond over our shared gifted tendencies.

According to the National Association for Gifted Children, gifted students can be identified as “Students [who] perform—or have the capability to perform—at higher levels compared to others of the same age, experience and environment in one or more domains.” The title of “giftedness” should not set the students it is given to on a pedestal, but instead gives a deceptively simple label for the complexity and uniqueness of a gifted student and how their brains work differently than others, and in some situations,“different” is not a positive trait.

Those who possessed the ability to cruise through classes with minimal effort at a young age are at higher risk to experience detrimental effects in high school and college. Once the difficulty of classes begins to increase, so does the workload, and suddenly the student begins to fall behind. Many students who were able to excel in their earlier years of school without putting forth as much effort as their classmates often lack majorly in the part of learning effective study skills.

As the Institute for Educational Advancement says, “Many gifted students have never really experienced a true academic challenge during high school… Therefore, when these students encounter the more rigorous and demanding curriculum of college, they may be without the effective study skills and habits necessary since colleges require more application of concepts rather than just memorization of facts.”

The correlation between giftedness at a young age and the absence of application of knowledge is clear simply because if students are not challenged from a young age, developing a solid work ethic is no easy task. Adapting to the advanced classes and new challenges is truly a learning experience and is a skill that may take time to develop.

Although the big question of how to navigate the effects of premature giftedness does not come with a distinct solution, it is important to recognize the outcome of a gifted education from a young age.