How free speech has shaped America

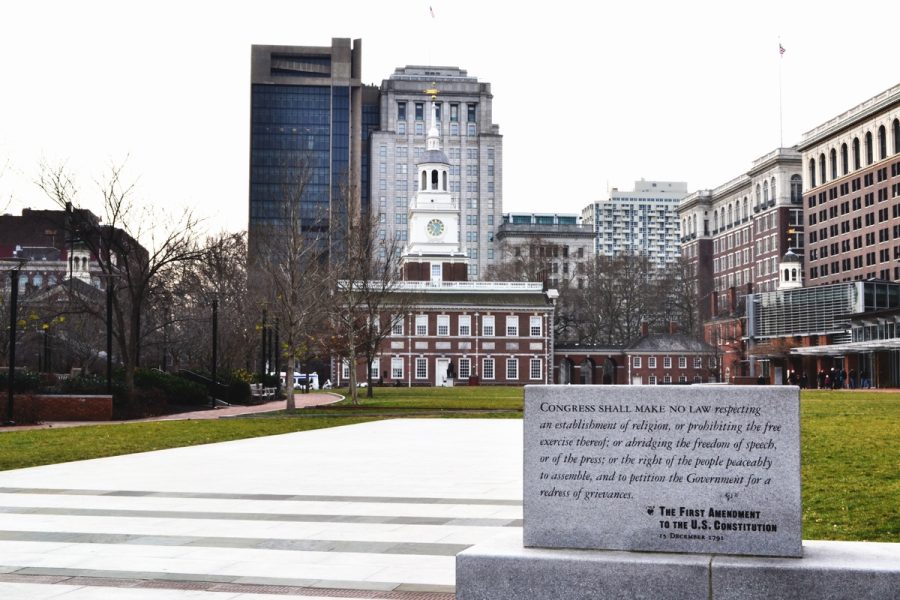

Wikimedia Commons / Robin Klein

Freedom of speech and press in particular are vital for posterity; the First Amendment freedoms are carved into this tablet in Philadelphia.

December 3, 2021

The history of free speech and press in America is one of repeated fluctuations.

This turbulence, however, should not and does not diminish the great importance of robust First Amendment rights. Regardless of the medium, the right to express one’s opinion is a hallmark of democracy. Yet America has not always been perfectly true to that ideal long enshrined in our Constitution. To understand contemporary issues of free speech as with Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange et al., we must first understand the limitations of free speech throughout America’s past.

22 years into our country’s history, Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1798, which allowed for the imprisonment and deportation of anyone publishing “false, scandalous, or malicious writing” against U.S. policy. It was an era of slander, exaggeration and occasional libel in newspapers; that is true. The act’s goal was to unify the country under support of the government, but it merely stifled criticism, limited First Amendment freedoms and further divided the nation. It also heavily contributed to Thomas Jefferson’s unseating of the Federalist incumbent in 1800, which greatly shaped U.S. policies for decades to come. Though the Sedition Act expired in 1801, it nonetheless ignited a vigorous debate about the extent of constitutional free speech protections.

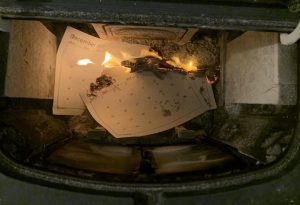

Three score and three years later, Abraham Lincoln was in the midst of the Civil War. In addition to suspending writ of habeas corpus, the president prohibited printing of news regarding military movements without approval. While these actions are perhaps understandable, less justifiable was Lincoln’s shutting down of the Chicago Times for significant criticism of his administration. Nationwide, 300 allegedly disloyal newspapers were terminated and many newspaper editors arrested. Some newspaper offices were even destroyed, as occurred with the Washington Times. Beyond the press, a prominent northern Democrat was arrested and later banished for delivering an anti-war speech. Historians generally agree that Lincoln privately disapproved of these latter actions but publicly did nothing. The president also ignored rampant corruption and patronage among the press and politicians, which greatly threatened independence and freedom of the press. Ultimately, even considering the Constitution’s presidential war powers, how legal and instrumental Lincoln’s actions were in saving the Union is still an open question.

In 1918, America was near the nadir of World War 1. As an attempt at preserving American security, Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1918 (adding to the previous year’s Espionage Act), which prohibited “disloyal, profane” language about the U.S. government, military or flag. Punishments included up to 20 years in prison. In practice, the law was often used by those in power to imprison political opposition figures, such as Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs. He and others were convicted of sedition merely for critiquing American involvement in the war. Even 27 S.D. farmers were convicted for petitioning the government to end the draft. Rampant convictions during this time led to many Supreme Court cases, perhaps most notably Schenck v. U.S., which ruled that the government could restrict free speech when it created a “clear and present danger” to the country. While this may seem a fair boundary to draw, we must ask whether public advocacy against conscription actually created a danger to national security. In any case, this legal standard was replaced by a test as to whether speech incites “imminent lawless action.”

The trend of using such terms as “sedition” and “treason” to censor progressive activists, as seen with Eugene Debs and Charles Schenck, continued into the Civil Rights Era. Georgia legislator and civil rights leader Julian Bond vocally criticized the Vietnam War, which prompted state officials to attempt to remove him from office. Eventually, the conflict worked its way up to the Supreme Court, which ruled that Bond could not lose his seat merely due to his political views. Later, Bond stated, “I think it is sort of hypocritical for us to maintain that we are fighting for liberty in other places and we are not guaranteeing liberty to citizens inside the continental United States.”

More recently, similar limitations of free speech or freedom of the press have occurred. Under the Patriot Act of 2001, no entity can provide what could be construed as support for state-designated terrorist groups. The federal government’s definition of support, however, is very broad and applies even to providing advice on peaceful conflict resolution. As NPR noted, “The nonprofit Humanitarian Law Project has a long history of engaging in such activity, mediating international conflicts and promoting human rights. But it has stopped doing some of its work for fear of being prosecuted under the material support provision.” Ironically, the group’s president, Ralph Fertig, was once jailed in the U.S. for his peace advocacy.

Much of the Patriot Act’s largest implications were revealed in 2013 by whistleblower Edward Snowden, who exposed a massive NSA surveillance network of U.S. citizens. Charged with violating the Espionage Act of 1917, Snowden is currently abroad in exile. But whether he is a patriot or a traitor, and whether his speech was protected or not, remains a matter of debate. The same questions apply to Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning, who disclosed classified documents regarding U.S. involvement in Iraq. Did they jeopardize national security, or did they act in the best interest for their country?

In any case, it is clear that free speech has been instrumental in shaping American attitudes, policies and lives. The First Amendment freedom makes this country a democracy and makes its leaders accountable. For the sake of both posterity and the present, we must all understand, acknowledge and exercise these rights. Only by doing this can we ensure a robust, lively democracy in which the voices and concerns of the many, not just the few, are addressed.