The forgotten murders of indigenous women

Photo used with permission by Canva/Katya Surendran

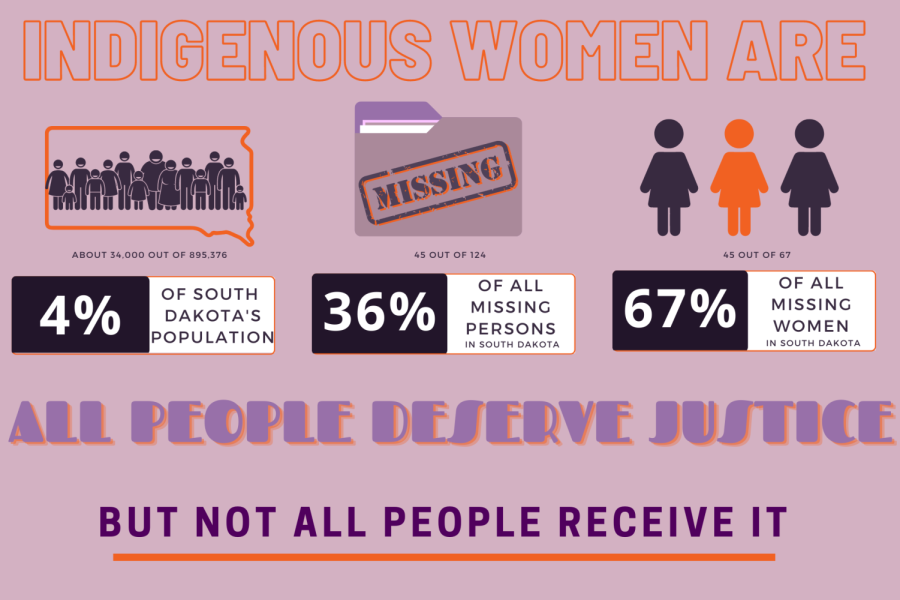

Of the 124 people on South Dakota’s Missing Persons List, 36.3% are Native women. Yet, indigenous women make up around 4% of the total, state-wide population.

March 1, 2023

In late Feb. of 2003, a 20-year-old Leslie Ironroad was found nearly dead, locked in a bathroom after suffering rape and several life-threatening injuries in McLaughlin, South Dakota. She died, later that week, at a hospital in Bismarck, North Dakota. Due to negligence, Ironroad’s case got mixed up in a pile of others and remains unsolved today.

Four years after her death, a NPR investigation discovered that before she passed away, Ironroad gave a statement to local authorities identifying the men who raped her. The case was never thoroughly investigated and no rape kit was ever done. No one was ever questioned and her murderers went unprosecuted. Ironroad never received justice.

Along with Ironroad, gaps in the investigation of other indigenous women’s missing person cases have allowed the perpetrators to get off scot-free. The limited response from the police and the media lessens criminals’ fear of being caught, making Native American women easy targets and disproportionately faced with the horrors of murder, kidnapping and human trafficking. The most vulnerable are those who lack resources, face poverty and are part of a seemingly voiceless minority. You are more likely to go missing if your kidnapper doesn’t think anyone will make the effort to find you.

Missing person cases concerning America’s indigenous women go unreported in news articles and in the data, making thousands go forgotten as if they were invisible to begin with. These cases are rarely covered by any news outlet and are rarely given priority equal to that of other missing cases. According to the Attorney General’s Missing Persons page, of the 124 people on South Dakota’s Missing Persons List, 36.3% are Native women; similarly, of all missing women cases, 67% are Native American. Yet, according to the United States Census Bureau, indigenous women make up around 4% of the total, state-wide population. The disproportionate disappearances of Native American women are explained by the fourth estate’s captivation with the missing rich and white. Society, in turn, limits its focus, letting indigenous women go missing for the second time.

In 2019 and 2020, the Not Invisible Act and Savanna’s Act were implemented to ensure a more coordinated response to missing indigenous cases between tribal, federal and local law enforcement. However, little has been done to combat the epidemic that is human trafficking. Along with trafficking, missing person rates for indigenous women continue to rise. Law enforcement and the media cast a perpetual shadow on young indigenous women. Even though a little light has been shed, this problem hasn’t touched the minds of the public enough to result in real change. Each missing person should be as important as the next. But they aren’t.

According to the Attorney General’s Missing Persons page, there are currently 45 missing Native American women and girls in South Dakota. It is not enough to simply spread awareness, we also need to fight for the rights of missing indigenous women. These women deserve to have their stories told and their wrongdoers found. They deserve justice, not namelessness. Thousands of people will continue to experience the atrocities of human trafficking if we continue to treat young Native American women as invisible, second-class citizens.

Ironroad deserved more than what she got. The people who should have been in charge of her investigation pushed her murder aside as though she was just another victim on a long list of frequent occurrences. Ironroad was a person, and she doesn’t deserve to be forgotten.

Stephanie L • Mar 23, 2024 at 8:56 pm

Thank you for sharing

Littledove Blackthunder • Mar 2, 2023 at 2:13 am

Due to prejudice and Knowing that of it was White or any other race. Of course they will let them go. And use the background check, of she was on illegal drugs or using alcohol cut down Native Americans, will the White Man or any race can be a Rapist or Pedophile and get away with it.