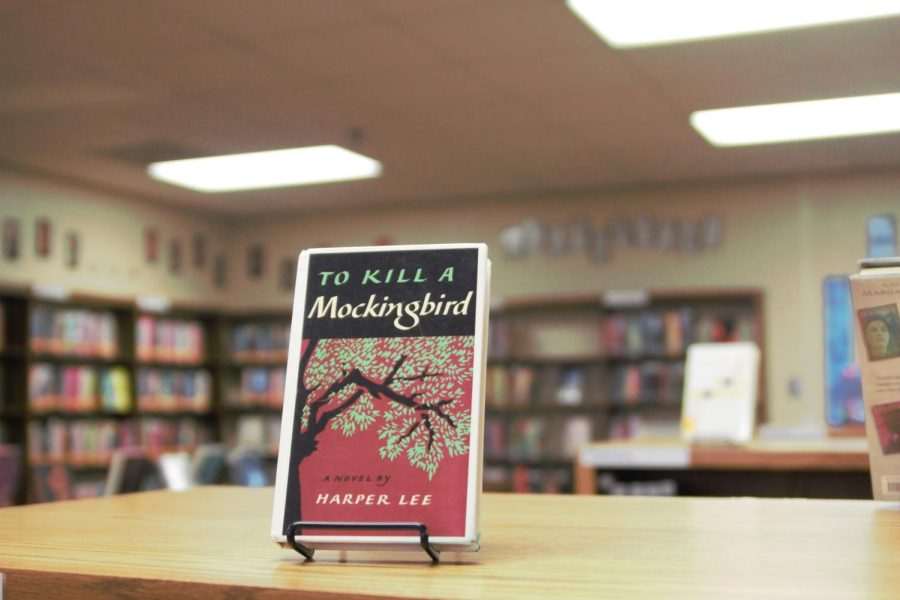

The real sin in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’

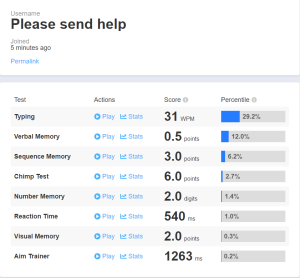

Out of the 281 pages, Radley’s name was mentioned 171 times, while the name Robinson, the mockingbird, was written for a low total of 69 times.

March 13, 2023

Across the nation, students are forced to read the so-called revolutionary novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird,” as the writing remains a literary marvel, but its message has eroded into a superficial discussion on racism.

Published in the year 1960 by Harper Lee, this story has been praised, criticized and even banned. “To Kill a Mockingbird” follows the life of a young girl nicknamed Scout growing up in Maycomb, Alabama during the early 1930s. She watched as her father, the legendary Atticus Finch, defended Tom Robinson, who was unjustly accused of rape. Scout experienced the effects of racism when her father became the attorney of a black man whom the white community had deemed guilty. Her neighbors, friends and family resented Scout for her father’s position. However, this was only a small fraction of the story.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” rose to fame because it explores the way racism can erode relationships and affect everyone, including children. The book declares prejudice a detrimental threat to society in an incredibly gentle manner, as if Lee was trying not to scare off her readers. “To Kill a Mockingbird” won the Pulitzer Prize because it treated the topic of prejudice with care. While focusing the story on Scout’s life in Maycomb, the message about racism gets lost in all the other noise like a tiny footnote at the bottom of the page.

This novel is far from revolutionary. “To Kill a Mockingbird” barely focuses on racism, prejudice or society. Robinson is the mockingbird who made the book famous, but more than half of the story’s readers wouldn’t be able to recall his name. Every person of color was a side character. Centering the attention on Scout and only on Scout, the Pulitzer-prize-winner mostly follows her obsession with Boo Radley, her mysterious next-door neighbor. Every man, woman and child who has read “To Kill a Mockingbird” remembers Radley, but not Robinson. The summary makes the story out to be some amazing tell-all of racism, but out of 281 pages, maybe 30 were about the nominal hero of this story, Finch, trying to save Robinson from unjust punishment.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” contains little substance, and it is a wonder that students across America are forced to read it even when its lessons find greater importance in other narratives. Why are we, as a society with centuries of knowledge on systemic racism, still reading a book about a child’s opinions on it? In the past, the story purposefully shined minimal light on the plights of a colored person, causing it to have no significance today. Children these days know far more about prejudice than Scout ever did. You’d be better off talking to one of them about racism. Or just maybe, you could learn from the perspective of an actual person of color instead of gathering information through the viewpoints of privileged saviors.

Despite the limited focus, Lee wrote beautifully in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” depicting family life in the South during the 1930s with impressive use of the English language. But, she wasted ink on trying to oversimplify the ugliness of racism, a disease the 21st century has become far too familiar with.