90-year-old Dianne Feinstein passes away, Mitch McConnell freezes up twice while speaking, and Mitt Romney will not run for reelection citing a need to make way for a “newer generation of leaders;” these circumstances beg the question, is the American government too old?

It’s no secret that demographically, the U.S. government is no spring chicken. Around a quarter of Congress is older than 70, which is the highest percentage ever in U.S. history. The baby boomer generation alone, those born from 1946 to 1964, make up 60% of the Senate and 44% of the House, while only representing about 20% of the U.S. population. In contrast, only 5% of Congress is 38 years old or younger, despite that age demographic making up half of the U.S. population. Suffice it to say America has come a long way from its youthful founding fathers, some of whom weren’t even of legal drinking age, by today’s laws. Might this be a cause for concern? If a competent and representative government is a priority, then yes.

The rising age of government officials has been a hot topic in recent years given that many politicians seem to be content working well into their old age. Senate Minority Leader McConnell is just one example of this obstinacy. He decided to finish his Senate term despite not one but two health episodes this year that left him frozen and unable to speak. 82-year-old Bernie Sanders has also chosen to continue his career as a Senator despite his 2019 heart attack. Senator Feinstein served in Congress up until her death in September, becoming the longest-serving female Senator, the list goes on. Not to mention that both Donald Trump and Joe Biden, who are 77 and 80, respectively, are running for re-election in 2024.

With geriatric leadership, it’s no wonder most Americans favor mental competency tests for politicians over age 75. As human brains age, they experience declining levels of neurotransmitters, impaired circulation of blood glucose and changing hormones, all of which affect a person’s ability to focus, recall information and learn new information. Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to question the capability of those in their 70s and 80s to function as competent leaders. After all, the retirement age in the U.S. is in the mid-60s and most people would prefer to retire somewhere that provides mental rest (like, say, a tropical beach) rather than the Senate floor. Some might even suggest implementing age limits for those holding public office or imposing term limits to cap the long-running careers of some of Congress’s more senior members.

Americans want younger leaders; 79% of U.S. adults support maximum age limits for elected officials and only 3% say it’s best for a president to be in their 70s or older. As such, a congress that resembles a retirement village is not exactly the ideal scenario. Not only are elderly congressmen a concern for reasons relating to their physical and mental ability, their politics have also proved to be troublesome. As Romney put it when announcing his future career plans, or lack thereof: younger generations are the ones who will be dealing with the effects of today’s political decisions. This has proven to be a sentiment many young Americans echo.

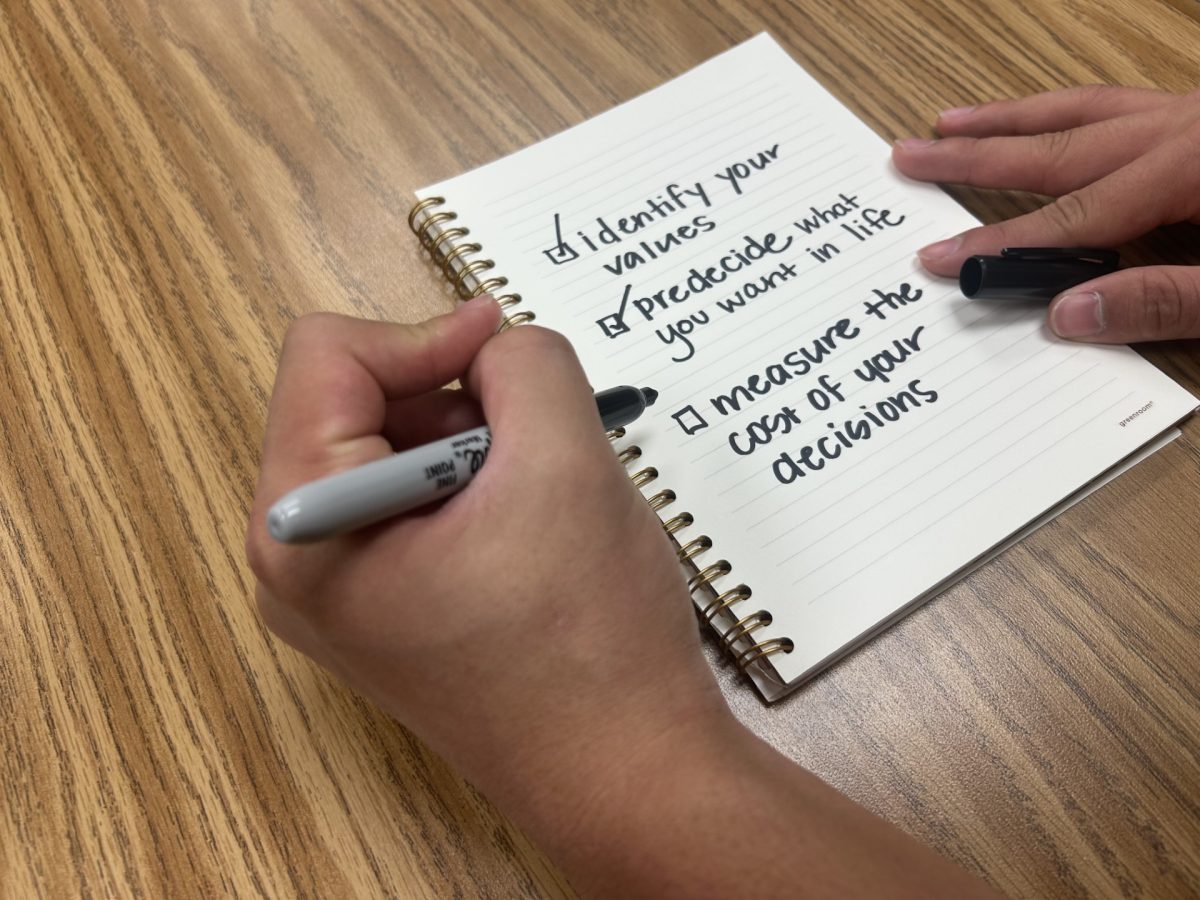

About two-thirds of young people say they are extremely or very excited to vote for a candidate who cares about the issues that affect them and their generation. For Generation Z and Millennials, these issues include healthcare, race equity, student loan debt, mental health and climate change. Younger generations often feel they can’t relate to the beliefs of the Silent Generation, Boomers or even Gen X’ers. This is to be expected, naturally those who were raised in different times have different ideas, values and politics. Each generation has its own priorities that are constantly evolving, which is a long-standing historical trend.

If you lived through a historical event like 9/11, the issues of terrorism and war overseas might be close to your heart. If you grew up during the great depression, it probably affected your views on economics. And if you lived through a crisis like the 2008 housing market crash, you might favor stronger regulations and transparency from banks. LGBTQ+ issues, for example, are likely to be higher on a Gen Z-er’s list of priorities than someone from the Boomer generation who grew up before gay marriage was legalized and before the advent of pride parades and drag shows. Needless to say, coming of age in the 1940s during the postwar boom is very different than growing up in the 2000s alongside the rise of the internet and social media.

These cultural differences help to provide a necessary diversity of ideas and perspectives within our government; however, the rift they cause in intra-generational relations is undeniable. With such a large chasm between generations, it’s no surprise young Americans have a longing for change: a lack of political alignment seems to necessitate a shift to leadership more congruent with the U.S.’s youthful demographic. Older elected officials don’t always embody the future that Gen Z-ers imagine for themselves. It would seem more logical to have lawmakers who represent the future of the country rather than those who create policy, the consequences of which they may never see.

The capability of senior American officials remains hotly contested. However, politicians like Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, the youngest woman ever elected to Congress, and Maxwell Frost, the first Gen Z congressman, may be signs that our country is turning over a new leaf.