Try to summarize culture; without language, it is futile. Words make it possible to teach, learn and pass on tradition. But what happens when elements of a dialect start to dissipate or are taken over by a dominant language, becoming endangered?

Out of over 500 Native American languages that once existed, only 100 are still spoken and Lakota, or Lakȟótiyapi, is one of them. Classified as endangered, Lakota is part of the Sioux, or Oceti Sakowin, language spoken by Native Americans from the Great Plains region. The largest of the Sioux dialects, Lakota holds a unique position as one of only eight Native American languages remaining with over 5,000 speakers, according to the Lakota Language Consortium.

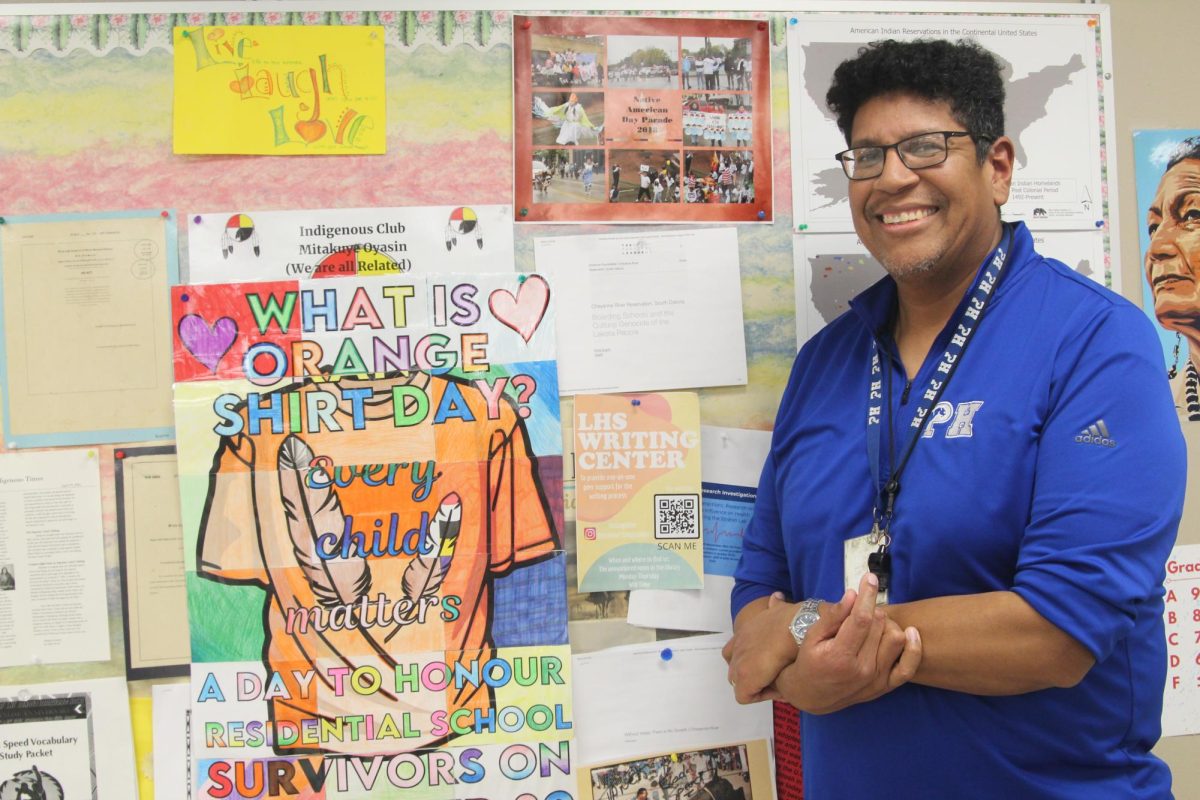

Tim Easter understands this issue personally as an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux tribe based on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Easter works as the Lakota Language teacher for LHS and WHS within the Sioux Falls School District. He also teaches Oceti Sakowin classes at Patrick Henry Middle School and Native American Studies at the USF. Easter’s mother is a fluent speaker of Lakota, which is her first language, her second being English. Because of his heritage, Easter grew up close to the language and had an interest in it, inspiring him to teach others.

Although a few of his students have family members who speak some Lakota, Easter finds that today, fluent speakers are few and far between. Easter teaches two levels of Lakota classes for the district with around 12 level-one students and five level-two students. While his class sizes may be small, for Easter the ability to offer native language classes is a special one.

“What I really appreciate with the school district is being able to offer this class along with French, Spanish, German and some of the other world languages so that students can see value in it, that, ‘oh okay this language is important’ and that it’s a language that should be learned,” said Easter.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, over 500 government-funded boarding schools throughout the U.S. were dedicated to the assimilation of Native children into modern American culture. Often under the threat of abuse, children within these institutions were prohibited from practicing their native culture. Forced to learn and speak English, Native American communities suffered a loss not only of language but of cultural identity, the impacts of which can still be felt today.

“[Lakota has] obviously changed, for good or for bad,” said Easter. “In reference to the boarding schools…there were some of the traditional aspects that were lost. And instead, there were put in new priorities or new cultural things, be it religion, be it mainstream American culture. So, there might be some sayings or phrases that were not traditionally Lakota but have been introduced just because English is such a dominant language…And maybe not so much the words but more the thoughts and how you would phrase something.”

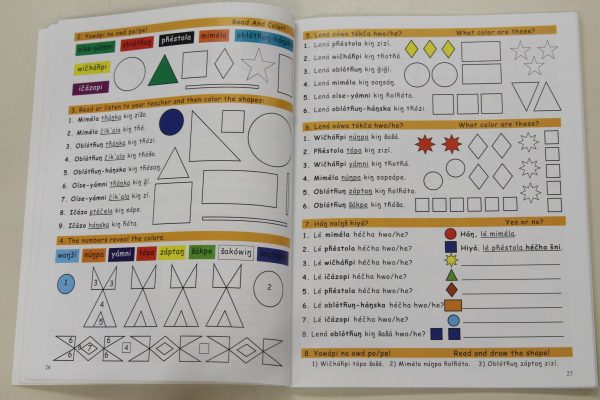

Teaching an endangered language comes with its challenges; Easter sees multiple obstacles facing Lakota language progression, one of which is a lack of extended vocabulary development.

“I think about when students go to school from kindergarten all the way up through 12th grade, how much more vocabulary is learned when going to school in English. But for Lakota speakers, it kinda stopped right at kindergarten in that there was no more progression in the language,” said Easter.

A lack of present-day Lakota knowledge necessitates translation to English, which has its drawbacks. When converting any language to another, there is a loss of connotation, context, significance and idiomatic expression, which also correspond to a loss of cultural elements. As such, efforts to preserve Native American culture are intertwined with efforts to preserve language.

“I am a true believer that you cannot have a culture without language, that language plays a vital part. There are things, words that are used, phrases that are used, that are unique to a culture, and that offer a perspective that English may not,” said Easter. “So even kinship terms, there’s meaning behind those. If we are referencing a certain person in the language, it has a story, it has meaning. Talking about the environment, indigenous languages had a way of explaining that may not translate as well or lose meaning when translated to English. So, when trying to preserve culture, when trying to preserve stories and traditions, customs and everything else, it is important to keep the language.”

One such example are the prayers Easter recalls hearing done in Lakota at indigenous events as a child, compared with modern English versions.

“It feels strange not hearing [prayer] in Lakota, but also knowing that there’s some of those things that are lost and there’s some of the meaning and the significance that’s lost when it’s not done in Lakota and instead it’s done in English,” said Easter. “English just doesn’t have that same feel.”

The nature of the Lakota language, which is practiced mainly by indigenous individuals and those who live on reservations, also creates a barrier for students. The scarcity of opportunity for those learning Lakota to get meaningful practice outside of school can stifle language advancement.

“I think, ‘okay how much of it is being spoken outside of the classroom?’…The hard part though is that if students and people aren’t speaking it outside of say, the classroom time, then it probably is [difficult]. We have a lot of students now that this is probably the only time that they hear and speak Lakota or interact with the language in any way. So, for a lot of the students as soon as they go home, it’s not spoken,” said Easter. “With Spanish, there’s probably opportunities, you could turn on Telemundo, or there’s any number of places that a person could speak and practice Spanish…there really isn’t that for Lakota, I shouldn’t say that there aren’t any, there’s just not as many opportunities.”

Lakota originated in the Midwest and, like other indigenous dialects, is still based there. Unlike more widespread languages, however, Lakota only has one active population as opposed to global communities. For Easter, this highlights the importance of protecting Lakota here in South Dakota. After all, these individuals represent the whole of what is left of native speakers.

“If somebody stops speaking Spanish, there’s still a place to go where Spanish is spoken. If somebody moves here from Norway and they stop speaking Norwegian, there’s obviously still a place that you could go where people are gonna speak Norwegian. Indigenous languages are here, so if people stop speaking it, where are you gonna go to hear people speak it?” said Easter.

As Native languages face challenges worldwide, it is important to remember the value of cultural diversity, something Easter has often touched on with his students. A multiplicity of ideas and perspectives ensures that over time, society remains diverse and does not succumb to homogeneity or noninclusive attitudes.

“There’s a lot of awareness of [loss of biodiversity]. So ‘save the whales, save the trees, save the rainforest, and save those things,’” said Easter. “And, those are important but I truly believe, and I would agree that there’s not as much awareness of lack of cultural diversity. So pretty soon there’s just this [opinion] that: ‘we don’t need to learn culture, we don’t need to learn language.’”

Easter believes this way of thinking is flawed, and that there is much to be learned from other cultures and mindsets both locally and around the world. However, in his experience, the priority simply is not there for some. 8.4% of South Dakota’s population is American Indian, but for those who are not, these issues are often out of sight and out of mind.

“For a lot of people, the argument would be: ‘well, we speak English, so why do you need to learn another language? Why do you need to learn another culture? ’cause we live here in the United States.’ But what we see though, is that culture is important,” said Easter. “So that way in 20 or 50 years from now, we’re not just this: ‘oh, okay, here’s 10 cultures and here’s three languages that are spoken.’”

A lasting legacy of assimilation policies and the negative impact of colonialism, Native American communities face disproportionately high rates of poverty, substance abuse and sex trafficking. Pine Ridge itself, the second largest reservation in the U.S., contains one of the poorest counties in the country: Oglala Sioux County, with about half its population living in poverty. While Lakota language degradation represents just one problem for this community, its preservation can make a difference.

“I do think that [language preservation] can help a group of people. If you have indigenous people, you have communities that are dealing with some of the social ills like poverty and homelessness, depression, things like that. Learning the culture and language isn’t the only answer, but it’s definitely something that could help with those [problems],” said Easter.

Easter finds that when it comes to problems facing Indigenous communities, solidarity is impactful. Even those who do not speak Lakota can make a difference through the acknowledgment of language and culture. Non-native individuals can show support in several ways, whether through wearing a colorful shirt for a day of awareness, taking a Lakota class or just being curious about the language and willing to learn more. Easter hopes people can acknowledge that this issue is important to others even though it may not be important to them.

“While a person may not practice [Lakota], it’s still important to acknowledge it. And if there’s a way for a person to support it in any way even by participation, they should definitely try it…Just that little bit of effort I think is something that everyone can do. And it would definitely help give the language and culture value,” said Easter.

Even amidst difficulties, Lakota persists. Easter has seen efforts to return to Lakota’s pre-colonization prosperity and bring back cultural aspects that have been lost. Easter remains encouraged by the fact that children and parents alike have shown interest in learning the language. The road to Lakota revitalization has been paved with several successes. Congress passed the Native American Language Act of 1990, furthering language education, and Red Cloud Indian School has been teaching Lakota language classes since the 1960s. With all Lakota has endured during its long history, it is teachers like Easter who help to keep the language alive, and prevent it from fading any time soon.